The Academy might have been staging its 85th Awards this year, but it’s only the twelfth time that it’s handed out an Oscar for the Best Animated Feature. Pixar has dominated the category, with films including Finding Nemo, WALL-E, Up and Toy Story 3 having walked off with the Oscar.

The Pirates, with subtitles of your choice, depending on whether you’re British or American, was made by Aardman at their Bristol studios, directed by Peter Lord. British animators Sam Fell and Chris Butler co-directed Paranorman at an animation studio in the US state of Oregon. These two, like the third film with British involvement, Frankenweenie, were unusually stop-motion; a welcome resurgence of one of the earliest traditions of animation in the day of computer generated images.This year, it was another Pixar film that triumphed, with the tale of a young Scottish princess, in Brave, taking the honours for directors Mark Andrews and Brenda Chapman. Although it’s very much an American studio, the film used Scottish talent for authenticity and it was one of four of this year’s five nominees that had a substantial amount of British input, highlighting the UK’s importance in the global animation industry.

Like the winner in the category, the final nominee this year, Wreck-It Ralph, was a CGI film from Disney, Pixar’s parent company, executive produced by the Pixar founder John Lasseter, who took the same role on Brave.

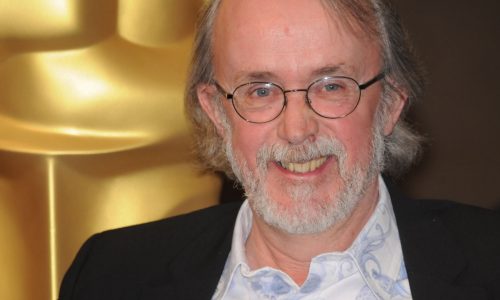

Days before Andrews stepped up to the microphone to accept his Oscar in a kilt, he joined the other nominees at the Academy’s Beverly Hills headquarters to discuss their films and the state of the sector. Compared with the directors of the documentaries and short films who’d attended similar events in the previous days, posing for photographs with a larger-than-life Oscars statue and doing interviews with the press, the animators were noticeably more animated. Pulling faces, posing like Rodin’s Thinker, dancing around the statue and even fondling its chest, contributors at the event – as in previous years – were themselves larger-than-life. A losing nominee from three years ago, Coraline’s Henry Selick, looks and behaves like he could have been one of his own characters.

The directors were similarly entertaining and energetic in the question and answer session, chaired by the comic actor Rob Riggle – a former Lieutant Colonel in the US Marine Corps – a path almost followed by Andrews, before he chose animation instead. Andrews didn’t see the fact that Brave was Pixar’s first film with a female protagonist as an issue, noting that the studio’s previous films have been centred on toys and robots. “What matters is the type of character,” he insisted, in his booming voice. Although at times he was talking seriously about his art, his booming voice – so loud that when he later contributed to the discussion from the back of the 1200 seater auditorium without a microphone, he could be clearly heard – often sounded comic. On that occasion he was reminding another nominee how the Disney animation boss John Lassiter responds to questions about when animations are ready to be shown to audiences: “We don’t finish films, we release them.” In his most serious moments, he was insisting that films should not be made for a particular audience. “That just screws everyone else,” he observed, insisting that you have to “make what you want to see,” He also criticised those who see animation as a medium for children, and he encouraged animators to continue to push the boundaries. In the lighter moments of the discussion, he observed that the inspiration for the film came from his co-director Brenda Chapman, who was having difficulties with her strong-willed six year old daughter. “What’s she going to be like as a teenager?” he remembers her asking.

The inspiration for Paranorman, as it’s name suggests, a film that features ghosts, came from Chris Butler’s grandmother. “Nana introduced me to the subject of death at an early age,” he remembers. “She said she’d be looking over me after she died.” He watched Night of the Living Dead at the age of 8 and sound found himself being drawn to films with the word “dead” in the title. “John Carpenter meets John Hughes” is how he pitches his film, which playfully introduces younger audiences to the horror references he and Sam Fell both grew up with. “Or Scooby Doo, directed by Sam Raimi.” While “every shot started with a puppet,” although it was a stop motion film, the pair were not frightened of using new technology. “We’ll use all the tools we have to make it as good as it can be,” Butler observed.

An American who’s made the journey the other way across the Atlantic is Tim Burton, whose films, both live action and animation, have frequently involved the paranormal, or at the very least gothic horror. His latest, Frankenweenie, about a boy who stitches up his dead dog and brings him back to life, was the opening film last year’s London Film Festival, and like Paranormal, paid homage to its many predecessors in live action horror. Known more for his humour on screen than off, Burton acknowledged having his arm in a sling before he began. “I just thought it looked cool. I was going to try an eye patch.” But despite having one arm strapped to his chest, he was still able to wave his other arm around enough to impress an orchestral conductor as he enthused about a project that took him back to his own childhood, in a cathartic way. “It was fun to go back, remembering the weird girls and scary teachers. The classroom set gave me an ill feeling.” Trying to explain his home town of Burbank to British colleagues, he remembered, “They thought I was talking about a different planet.” Asked why this was one of the few films he had done without Johnny Depp, he paused, shrugged and acknowledged, “He does good barking sounds. But no.”

While Fell and Butler made their film in the US, Peter Lord shot The Pirates right at home in Bristol. While he’s been producing Aardman’s output since the studio first opened its doors in the early 1970s, he hasn’t directed since Chicken Run, twelve years ago. “I never wanted to be a producer,” he noted. “It just happened. I had to direct again or I’d end up a producer for life!” Until The Pirates, he’d always been scornful of film makers who adapted books, but he said he’d never laughed so much when he read the source material for this film. Describing working with Hugh Grant as the main voice artist, Lord was open about the difficulty the pair had working together, as he tried to get Grant to act out of character. “It was difficult for both of us,” he recalled. “He wasn’t comfortable with the things he had to do.” He laughed as he described casting Jeremy Piven as his antagonist. “We were tired of Brits always being the villains, so it was a private joke to have the bad guy played by an American.” And he spoke with great pride about the studio’s continued embracing of stop motion, noting that at un-named studios where CGI is preferred, everyone’s just sitting around on computers. “At Aardman, we’re all playing with toys.”

Wreck-It Ralph was a more typical animation and Rich Moore was a typical animator, jumping up to walk across the stage when it suited an answer. His film was about computer game characters who come to life when the arcade closes at night, much as Toy Story was about toys who come to life when the children to go sleep. “A lot of people at animation studios like video games,” he observed wryly, with faux naivety. Disney had already given up on an attempt to make a film about video games when he arrived, so he picked up the project when he joined the studio. When he was putting the story together, rather than seek the rights to use characters from the games before he started, he told his team to pretend they had the rights to everything, so as not to constrain their creativity. He then personally set about seeking permission to use those he needed. “It’s better to make relationships than to have Disney lawyers do battle with Nintendo lawyers.” Moore has a background in TV, but he says animating for the big screen is different. “On TV, from the first day, you’re behind. It’s a sprint, trial by fire. It’s the best education you can get. But for film, you have a longer schedule. The characters need an arc and the project has to stand the test of time.”

After individually discussing their own films and processes, the directors joined each other on the stage for a group discussion about animation more generally. Tim Burton described how inspirational it can be. “I showed Frankenweenie to my kid’s class at school. The next day, they were making their own stop motion films.” The group shared their views on recording the actors’ voices – traditionally this is done one at a time, but Rich Moore said the voice of Wreck-It Ralph, John C Reilly, didn’t want to sit alone in a booth, so he tried to get as many of the actors together at one time. Burton’s main issue, working with children, was to get the voices recorded quickly. “If you need to call the kids back, their voices might have broken.” Peter Lord said animation was the definition of deferred pleasure. “After five years, you finally hear the laughter – you have to love doing it,” he added as he says he is as proud of the atmosphere in the studio as he is with the film. Moore too clearly loves what he does. “It’s dangerous to say, with people from Disney in the room, but I’d do this job for free.”