| Worth seeing: | as an unconvincing underdog legal drama that owes more to luck than logic |

| Director: | Tony Goldwyn |

| Featuring: | Hilary Swank, Sam Rockwell, Clea DuVall, Juliette Lewis, Melissa Leo, Minnie Driver |

| Length: | 107 minutes |

| Certificate: | 15 |

| Country: | US |

| Released: | 14th January 2011 |

WHAT’S IT ABOUT?

When simple farmhand Kenny (Sam Rockwell) is convicted of the brutal murder of a woman in a mobile home close to where he lives and jailed for life, his sister Betty Anne (Hilary Swank) is convinced of his innocence. With no other suspects, everyone else – not least the arresting officer Nancy Tayor (Melissa Leo) – is convinced of his guilt.

When all appeals lead nowhere, Betty Anne realises that no-one else is bothered whether he dies in jail, so the only hope he’ll ever have of getting out rests with her, learning enough about the law to defend him herself.

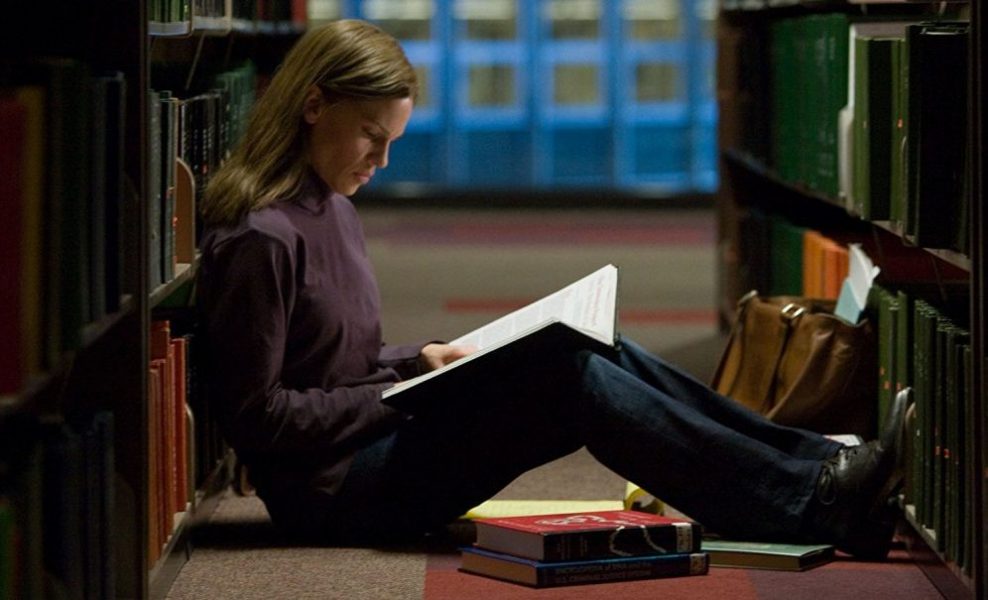

In an inspirational real-life story, despite being a busy mother of two and working in a bar at night to make ends meet, Betty Anne signs up to study law at the local university.

With the help of her classmate Abra (Minnie Driver), Betty Anne looks into whether this new fangled DNA technology can be of any use to her. But by the time she sets out to trace the original evidence, sixteen years have passed.

And even if she can prove that blood at the scene didn’t come from her brother, can she satisfy a court that he had nothing to do with it at all?

WHAT’S IT LIKE?

Somehow this film fails to hit the marks it sets for itself.

It’s clearly trying to be another Erin Brokovich, with a nobody becoming a hotshot lawyer, against the odds, and against even bigger odds, ensuring that justice is done.

But in this film, we have nothing other than her own faith in her rather dodgy brother to convince us that we’re right to root for her in the first place.

And most worryingly from a dramatic point of view, you don’t need to be a trained lawyer to do any of the things she comes up with. While DNA testing was in its infancy at the time, you wouldn’t have needed to study for several years to learn of its existence. Furthermore, given that evidence is – we’re told – usually thrown out after ten years, the fact that they found it after sixteen years is oddly fortuitous. And the events that follow seem so unlikely that it destroys all faith that this could possibly be a true story – and of course, it doesn’t take much investigation to establish that the film-makers have taken a liberty or two with the facts for dramatic purposes. So the conclusions to this story are more down to luck and common sense than any kind of judgement, based on years of study.

Hilary Swank’s earnest performance is engaging enough, but Sam Rockwell is never particularly sympathetic, Minnie Driver does no more than sit on the sidelines, fulfilling the supportive best-friend role by ‘helping’ where necessary (ie not very much) and Melissa Leo plays the stereotypical witch of an authority figure, who’s determined not to be proved wrong, as her own fallibility is a bigger issue to her than the rest of the life of someone who might, actually, have done nothing worse than be a bit eccentric, without an alibi.

Other layers of cinematic artifice, such a law teacher who puts the lid on a box of essays, as Betty Anne is running towards it, waving her paper in the air, just give this even more of a feeling of a disease-of-the-week-style family drama than any kind of worthy, world-changing polemic about miscarriages of justice; even if certain worthwhile issues are raised here, most of the breakthroughs have nothing to do with being a lawyer.

Some critics have condemned the film further for caring little about who actually did carry out the murder, although – in truth – a film about proving someone’s innocence is about putting right a miscarriage of justice, not about providing justice for the murder victim, hard as it is for surviving relatives to come to terms with.