| Worth seeing: | as a gritty piece of social pessimism that's easy to admire but difficult to recommend |

| Director: | Paddy Considine |

| Featuring: | Peter Mullan, Eddie Marsan, Ned Dennehy, Olivia Colman, Samuel Bottomley |

| Length: | 92 minutes |

| Certificate: | 18 |

| Country: | UK |

| Released: | 7th October 2011 |

WHAT’S IT ABOUT?

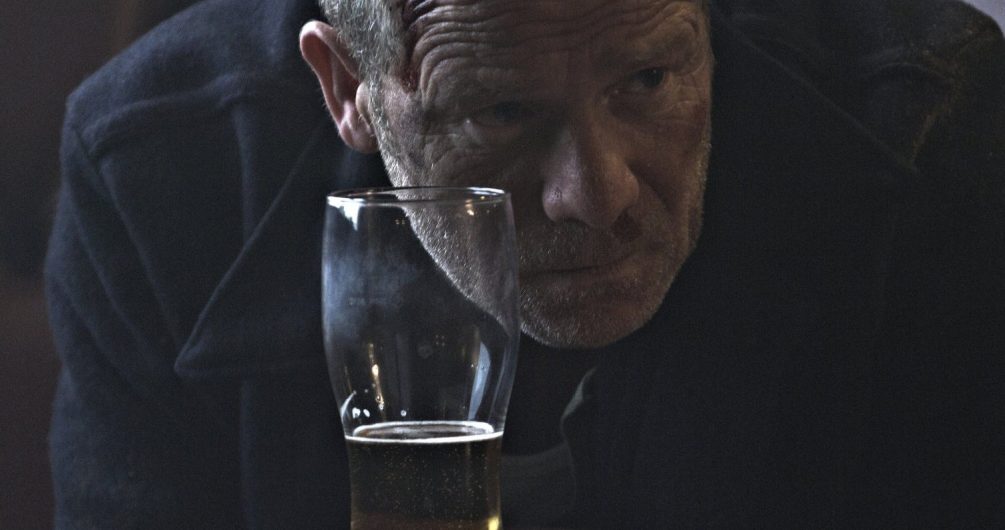

Joseph (Peter Mullan) is an alcoholic widower with severe anger management issues, living alone in a run-down house on the kind of housing estate that would frighten the middle classes.

After losing a bet on the horses, he kills his beloved dog in a rage and ends up picking a fight with a bunch of teenagers – and pretty much everyone else he encounters.

With each breath, his life spirals further out of his control.

In a moment of weakness, he seeks refuge in a charity shop, hiding behind a clothes rail. The owner, middle-class Hannah (Olivia Colman), takes pity on him and offers him a cup of tea and a shoulder to cry on and before long, an unlikely friendship has developed between them.

It’s more a friendship of necessity than respect. She’s a Christian and would, in truth, help anyone. And apart from his alcoholic drinking buddy Tommy (Ned Dennehy), and the sympathetic schoolboy across the road, Samuel (Samuel Bottomley), he has no-one else to talk to anyway.

But he craves the warmth he receives from her – even though he resents her comfortable middle class existence – until he discovers that her life isn’t as idyllic as he’d assumed. She turns out to be trapped in an abusive marriage to the sly James (Eddie Marsan).

Even when Joseph realises that he is Hannah’s escape as she is his, he finds it hard to open his heart, but he realises that the only way to improve his own life is to help Hannah improve hers.

WHAT’S IT LIKE?

Tyrannosaur is an emotionally wrenching film – not one to be seen if you’re feeling a little down on your way in – unless seeing people even more unfortunate than yourself lifts your spirits, rather than kills them off completely.

The two key performances – Peter Mullan’s helpless brute and Olivia Colman’s brutalised angel – are heart-breaking, but mask the fact that while there’s a lot of acting going on, there’s not that much else going on beneath it. And an astonishingly cruel and bitter Eddie Marsan makes a shocking antagonist, but he’s so black to Colman’s white that it nudges the characterisation a little too close to caricature.

There is almost no light in this desperately dark film at all – only the innocence of young Samuel across the road, himself abused by his mother’s boyfriend and his pit-bull, raises the odd uncomfortable but necessary smile. Without him, there’d be as much bloody spilt and as many tears shed in the auditorium as on the screen.

The drama builds at an effective pace, but it builds to a twist that feels a little too unlikely to flow with the rest of the film. It’s tough to accept that, even in these circumstances, people like this would actually resort to the means required to achieve the ends.

Paddy Considine is known to most as an intense actor – a close collaborator with Shane Meadows, as well as popping up in the odd big budget actioner, such as The Bourne Ultimatum. Most recently, he was seen stretching his little-used comedic muscles as the eccentric neighbour in Submarine, but for his feature-length directorial debut – based on his own BAFTA-winning short Dog Altogether – he returns to his comfort zone – a zone in which no-one is comfortable.

We meet so many miserable characters, few with any redeeming features. Where there is light, he extinguishes it. He seems to have an upsettingly bleak outlook on the world and delivers a depressing take which might be true to life, but you have to wonder who would pay to witness such unremitting misery in the knowledge that they will feel as downbeat at the end as the protagonists have felt throughout.

Most people watch such grim films in the hope of witnessing redemption – some positive degree of self-discovery – but your patience will be sorely tested and left unrewarded.

Tyrannosaur is very much the kind of film that you admire for its cinematic stubbornness, and artistic merit – the production-design is necessarily Spartan and dull, while its peopled with characters who alienate us as much as they alienate each other. The visceral performances will leave you shouting at the screen to stop the runaway train to let you get off – to breathe in some fresh air – to breathe.

It’s an impressive piece of film-making, but it’s difficult to recommend.

Paddy Considine is confident behind the camera – maybe overconfident. Perhaps now that he has spat out this pessimistic streak across the big screen, he can add a little more warmth and believable complexity to his future efforts.