| Worth seeing: | as a powerful portrayal of a group of black rights activists who fearlessly stood up to the racist establishment |

| Director: | Steve McQueen |

| Featuring: | Letitia Wright, Malachi Kirby, Rochenda Sandall, Sam Spruell, Shaun Parkes, Alex Jennings, Derek Griffiths, Gary Beadle, Gershwyn Eustache, Jack Lowden, Jodhi May, Joseph Quinn, Jumayn Hunter, Nathaniel Martello-White, Richard Cordery, Richie Campbell, Samuel West, Steven O'Neill, Thomas Coombes |

| Length: | 207 minutes |

| Certificate: | |

| Country: | UK |

| Released: | 15th November 2020, on BBC iPlayer and Amazon Prime |

WHAT’S IT ABOUT?

Born in Trinidad and Tobago, Frank Crichlow (Shaun Parkes) had become a stalwart of his west London community by the time he opened the Mangrove restaurant in 1968. It became a home-from-home for members of the West Indian community of Notting Hill, who wanted a friendly chat and a taste of the Caribbean.

But the local police – in particular, PC Pulley (Sam Spruell) – took exception to its growing popularity and repeatedly raided the restaurant, trying to find drugs or criminals, coming away empty-handed every time.

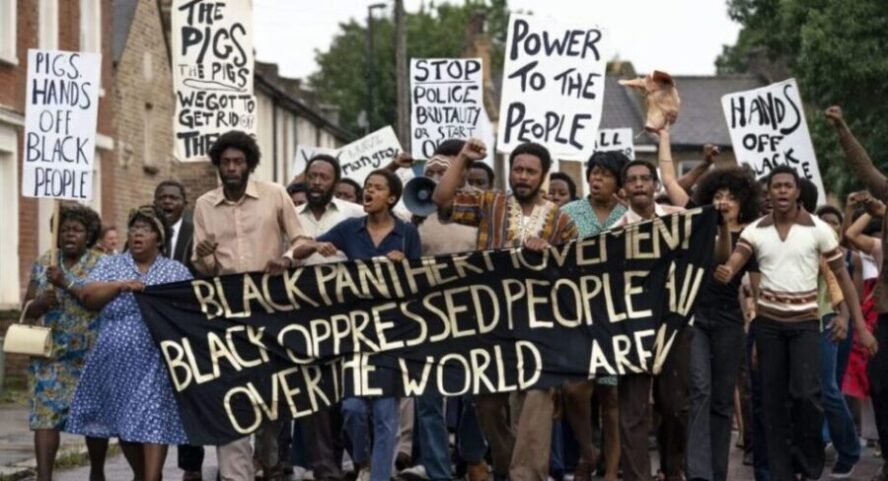

By 1970, the local community had had enough of being harassed by PC Pulley and his gang of racist officers and marched on the police station, carrying banners and shouting slogans. When police responded, the mood soured and nine of the marchers found themselves on trial, at the Old Bailey, for rioting and affray.

The group included Frank himself, a local Black Panthers organiser Altheia Jones (Letitia Wright) and law student Darcus Howe (Malachi Kirby) – who went on to carve out a high profile career in the media.

What prosecutors thought would be a quick trial dragged on for eleven weeks, until an unexpected and historic pronouncement from the judge opened the way to further accusations of racism within the Metropolitan Police.

WHAT’S IT LIKE?

Very much based on real events, Mangrove is the first of a series of features made for TV by the Oscar-winning film-maker, Sir Steve McQueen, to reflect life among Britain’s West Indian communities.

While made for TV, its selection by the abandoned Cannes Film Festival and the largely online London Film Festival – along with the closure of cinemas – has deservedly elevated it from small screen status to share the prominence of a theatrical release.

Fifty years on from the historic trial it portrays, it’s notable that this film debuted at the end of a week when the Mayor of London called for a review of whether the Metropolitan Police use their stop-and-search powers disproportionately against black people. Shocking as it is that after five decades, even if police aren’t still routinely beating people simply because of the colour of their skin, questions are still being asked about their treatment of ethnic minorities – but it’s clearly nothing compared with the situation in the US, where decades after the civil rights movement started to draw widespread public support, black people are still being shot dead by police.

Perhaps the contrast gives viewers a sense of complacency as they watch scowling police officers smashing furniture as they wrestle innocent black men to the ground – people might think “thank goodness it’s not like that now” – but in truth, you don’t necessarily get the sense, from this film, that it was even like that then, apart from a couple of overtly racist police officers, the others just seemed to be acting in line with warrants – the problem was that the racist police officers got away with lying to get the warrant.

The trial elicited the first judicial recognition of racism within the Metropolitan Police, although – even according to this telling of the story – it was more about individuals than institutional.

That said, from a dramatic point of view, watching a hard-working restaurant owner having his place smashed up as he’s taken away for questioning – again – is equally infuriating, whether it’s an isolated incident or whether it’s going on across London.

There are a few moments where you feel that part of the story has been missed – it jumps from 1968 to 1970 with little fanfare and it jumps from the verdicts being read out to an apparently incongruous judge’s sentencing statement – but perhaps one of the most glossed over elements of the story is why a police officer who’s been in the force for seventeen years without a single promotion from the lowest rank seems to wield so much power and authority in this corner of west London. Are his bosses scared of him? Do they agree with him? Do they genuinely believe him, despite raid-after-raid ending with nothing? Perhaps it’s the lack of apparent logic that makes the situation so frightening – suggesting how people in authority can get away with appalling behaviour with impunity for so long. Even when the central characters are vindicated, there’s no punishment for those who put them in the dock in the first place. What’s even worse, in fact, is the “what happened next” captions, which show that even after this high profile embarrassment for the Metropolitan Police, the harassment of the Mangrove continued unabated.

But unlike the stories of racism coming out of the US – past and present – no-one gets killed here – no-one is even wounded – on either side. But perhaps the constant drip-drip of shameless inexcusable humiliation is worse than one-off murders or lynchings, as it betrays an ongoing, long-term problem of insidiously normalising the police brutality.

Alex Jennings’ trial judge helps us get to what’s going on; at the start of the trial, it seems like he is drawn to siding with the prosecution – surely the police wouldn’t make up their stories – surely the black agitators were just making trouble as you’d expect them to – and he doesn’t take kindly to what he perceives as their efforts to undermine his court. But by the end, the evidence is so overwhelming – or underwhelming, depending on which side of the argument you are on – that any prejudice he might have – based on his years of experience at the bench – simply evaporates.

Perhaps the strongest performances – from a powerful cast – are the delightfully contrasting Shaun Parkes and Malachi Kirby, as the unassuming restaurant owner who just wants to be left to get on with his life in peace and the eloquent but verbose, wannabe barrister and broadcaster, Darcus Howe, who seems to be as interested in showing people how clever he is as he is in clearing his name; it’s like watching a young Darcus Howe himself.

Sir Steve McQueen’s use of music – from the reggae beats in the restaurant to the steel drums being played on the streets – form a perfect aural backdrop to the narrative, conjuring up thoughts of the Notting Hill Carnival, which for a time was run from the very same restaurant at the heart of this story.

Mangrove is powerful and passionate story-telling – a film that feels like it’s been waiting for years to burst out of McQueen, who’s previously told us about the history of others – Northern Ireland’s Troubles in Hunger and America’s slave trade in 12 Years A Slave – but is finally telling us about his own. But what viewers take away from the film – whether it portrays a shameful piece of history or a frightening reflection of the present – will depend on their own background and experience.